Hello,

I’d like to share my thoughts on this topic. In my view, the first step is to remove the word “race” because of how it’s interpreted by the general public. For example, when I say “football,” you probably imagine a sport with 11 players on each side whose main objective is to score more goals than the opponent (yes—the real football, not the “hand-prolate-spheroid”). But when you say “race,” people often imagine separate species, like sunfish and barracuda. Yet the human species is a single race. Using the term “race” to categorize anything outside of phylogeny, in my humble postdoc opinion (PI > PhD Student > Master Student > General Public > Postdoc), is inaccurate and risks fueling some of the worst ideologies in human history.

That said, the concept often labeled as “race” can still provide indirect insights into other factors that are frequently overlooked. Many genetic studies fail to incorporate key demographic variables such as income, education level, and lifestyle factors, and in such cases this variable is sometimes used as a rough proxy. However, even this approach is problematic, because the challenges faced by members of any group differ from one individual to another, which can lead to misleading or distorted conclusions.

One example is a paper that I worked in 2015 (https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.06609). I will put some small pieces of it:

“Previous Brazilian studies, based on ethnoracial self-classification, reported greater prevalence of high blood pressure or hypertension among self-reported black adults and among blacks who reported having discrimination.”

What was the conclusion?

“Among those with African ancestry, 59.4% came from East and 40.6% from West Africa. Baseline systolic and diastolic blood pressure, controlled hypertension, and their respective trajectories, were not significantly (P>0.05) associated with level (in quintiles) of African genomic ancestry … Lower schooling level (<4 years versus higher) showed a significant and positive association with systolic blood pressure (Adjusted β=2.92; 95% confidence interval, 0.85–4.99). Lower monthly household income per capita (<USD 180.00 versus higher) showed an inverse association with hypertension control (β=−0.35; 95% confidence interval, −0.63 to −0.08, respectively)”.

In this work, you can see how using the term “African race” was harmful. It’s possible that “non-African” individuals with low income or lower education levels were overlooked because the association was misattributed to the wrong category.

For this reason, I advocate for improving data collection so that we gather the actual demographic and environmental information rather than relying on a proxy that is noisy and imprecise. For example, when I had to fill out a form to enroll my daughter in school, “race” was a mandatory field. I ended up having to select both “white” and “black”—and believe me, my daughter is not a Dalmatian. I honestly don’t know what kind of study they plan to conduct with such data, but my daughter is a statistical noise.

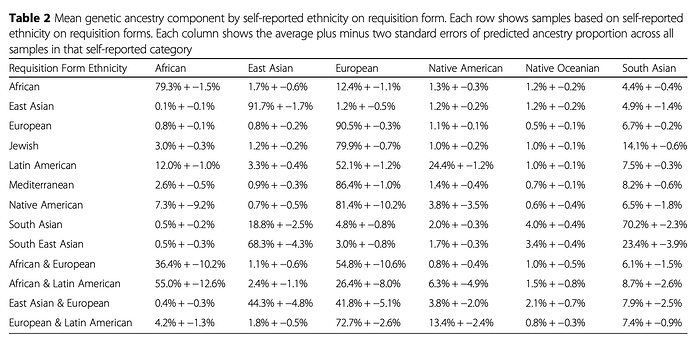

If you have genetic data (and a good team—I’m fortunate to have both), you can infer genetic ancestry. Ancestry is a much better term because it doesn’t divide humans into different races; rather, it recognizes a single human species with diverse geographic origins.

However, this leads to another challenge: how should ancestry-specific effects be reported? That’s a complex topic, and it will address it in another post.